The Mud, etc., Part 2

The Motor City’s Burning: John Lee Hooker

The Detroit riots or uprising as they have become subsequently known, were a scary time and tough for me, not yet 6 years old, to understand. But my parents explained that Black people were unhappy with white people and were burning down parts of the city. As shorthand accounts go, that was fairly accurate. The police and fire department were getting shot at and the army and national guard had been brought into the city to stem the violence. There was no rioting in our neighborhood on the East Side. My house was at 6 1/2 mile road, situated between Osborn High School, the Mt. Olivet Cemetery and the Detroit City Airport, our neighborhood landmarks. In 1967, the neighborhood was still entirely white, mostly Polish and Italian families, and we knew so many of the neighbors from our church and Catholic school at 6 mile road, Our Lady of Good Counsel. We were the Good Counsel Cougars before cougar took on a slightly tawdry meaning. It was a seemingly more innocent time of paper drives, and church fairs with fundraising raffles and rides like the Moonwalk where kids could literally bounce around like maniacs in an enclosed stinky feet environment and fly into one another feet first — consequences be damned.

There were some non-Catholic families in the neighborhood, many of them people who had moved up from Kentucky, Tennessee or West Virginia, white Appalachians. My mom tended to refer to these families as hillbillies, even though my father’s family had moved from the Appalachian coal mining town of Shaft, near Frostburg, Maryland. Mom’s family, Polish and Slovak, had been tenant farmers in central Michigan, until her father died when she was six. Her mom was alcoholic and made her way to Detroit’s skid row and a series of violent boyfriends. So, my mom was raised initially by her grandmother, and then after she passed, with her mom again, until Child Protective Services removed her from her mother’s home. After that, she was in foster care, and then by the time she was 15, living with her sister, my Aunt Anne, two years older than her and already living on her own and working in diners.

My mom’s hard childhood made her a tough woman, and she needed to be. Her first husband, Jack Machleit, the father of Gordie and Cindy (thus, my half-brother and half-sister), died when he was just 25 of a sudden and massive heart attack. It put into her mind the idea of always expecting the worst possible outcome. She even explained to me her version of her belief in God, which I later learned was called Pascal’s Wager. It was better to believe in God, because if there was no God and you did not believe, there were no repercussions; BUT if there was a God and you did not believe in Him, the consequences were severe. The smart money is on God. That was why mom was super religious, her unwitting knowledge of French philosophy. Notably, Blaise Pascal was born in Clermont-Ferrand, France, so he was perhaps destined to have an impact on our family since I later adopted the stage name Clermont Ferrand. Also unwittingly, at least to the Blaise Pascal connection. Fate?

Once, when my sister actually won the lottery, not the big mega-millions but nevertheless about $175,000, my mom’s reaction was “Keep in mind, she is going to have to pay income tax on that.” She was right, but it was still good to win some money. My sister got the money, paid the taxes, paid off some credit card debt, saw Barbara Streisand and treated her friends to a trip to Chicago. Not bad.

Do You Believe in Magic?: The Lovin’ Spoonful

A few years after the death of her first husband, my mom, Evelyn, married my dad, William, whom she knew from their old East Side Detroit neighborhood and high school, St. Rose. They were a good-looking couple. My mom with her dark brown hair, brown eyes and a nice figure, and my dad with blue eyes, thick black hair and a boyish handsomeness that got him comparisons to the screen star Tyrone Power. I was always proud of how handsome they looked together. As time went on, I noticed how square they were compared to the changing times. They were not changers. I suppose that is why they saw the Vatican Councils as so misguided. The Catholic Church was not about changing, until it did, but they didn’t.

I was born one year later. But Gordie and Cindy kept the surname of their dad, “Machleit.” My mom later explained, that was so she could continue to collect social security benefits for them. It was a practical decision but perhaps in the long run not the best because it only served to make manifest the difference between my brother and me. I got along well with Cindy, but Gordie never seemed to like me. I felt it was because I was a Carney and my dad was alive and his wasn’t. I tried not to feel bad about it and thought, it’s not my fault, but it was always a thing standing between us, just as our surnames remained different. It was never anything that dissipated with time. If he was not going to have his dad, I was not going to have an older brother, or even a half-brother.

Our neighborhood was full of houses mostly built after the war. Small-sized bungalows and ranch-style houses with driveways, one or two-car garages, and little yards in back. There were alleys behind the houses for garbage pick-up, and these were great playgrounds and private roads for us kids. We did a lot of playing in the alleys and that is where I once came across a large box of hardcore pornographic magazines with my friend Jim Robinson. I kept going back to that alley thinking it was somehow magical, like it was a portal to more interesting stuff, but that was a one-time event. That is the nature of magic. It doesn’t happen regularly.

Most houses had great, tall stately elms in front of them that created a canopy so dense and magnificent that we would walk under them during rain showers on our way to and from school and barely get wet. It made the neighborhood look like some sort of idealized form and illustration of what a model city block should look like. In fact, for a time Detroit was considered a model city with its booming factories and good paying jobs, even for men with little education. And it seemed that the sports teams reflected the city’s booming successful nature. The football team, the Lions, won the NFL Championship three times and the hockey team, the Red Wings, won 5 times in the 1950’s.

I was about 12-years old when the neighborhood elm trees were stricken with Dutch Elm disease and endured two or three summers of the sound of the chainsaws and the city cutting them down, in a strange effort to save them. It happened throughout the city and was eerily similar to our “strategy” in the Vietnam War: destroying the trees to save them. It left Detroit like it had been hit with multiple waves of Agent Orange. Almost all the trees were just one kind, giant elms. Those were great shade trees and people had not really thought to diversify. So, the neighborhoods transformed dramatically and were suddenly without any trees. The death of the trees seemed to foreshadow the devastation that would happen to so many neighborhoods in Detroit where first we lost our trees and then over time the houses became abandoned, boarded up, stripped of any copper or metal, burnt out, and then the lot was simply empty and a vast urban wasteland where once houses had stood side by side for blocks on end.

They had built a system of freeways throughout the Motor City, of course. Most of them had auto company-related names: the Ford Freeway, the Chrysler Freeway, the Fisher Freeway, and later the Walter P. Reuther Freeway, named after the labor leader. I heard that the interstate freeway system was put into place by President Eisenhower, in part, because of the fear of nuclear war and having to evacuate cities quickly in case of a nuclear attack. In truth, there was no actual nuclear attack, but it facilitated white flight from the city and left behind an urban core that sometimes seemed like it had gone through a horrible attack.

Ticket To Ride: The Beatles

I learned to ride a bike at age five, and my parents gave me free rein to explore all over. Free reign in a childhood kingdom. Perhaps that was because I was the youngest and they were used to my older sister and brother doing things on their own, but also because they thought that I was level-headed and could take care of myself. I think that with time I proved myself less “sensible” to them but to me that was just growing up. I was certainly lucky that they let me roam as a child and even in my teens where I explored areas of Detroit beyond my neighborhood. At the same time that I was granted so much autonomy to explore and play outdoors, my parents also okayed my checking out books aimed for adults from the library and told the librarians it was alright. So I was granted to license to roam among books without being confined to the normal roster of kid lit.

Dinners were somewhat somber affairs. My mom taught middle school math in the Detroit Public Schools in a central Detroit neighborhood with mostly black kids and Chaldeans, Christians from the Middle East that were a big population in Detroit. The Chaldeans, like so many immigrants before them, mostly operated small businesses like party stores (the name for our corner stores) or gas stations and they all lived in the same neighborhood. Mom would get home and put some food together for the four of us. My father would get home from work at five and change out of his clothes, he wore a white shirt and a tie at his accounting job at Detroit’s Water Department, and we would eat our dinner, or supper as we called it, at 5:30 p.m.

I got home from school about 3:30 p.m., before my mom was back from her school, and during that time my brother, who hated me, would terrorize me. Even as a kid, I was like, “what’s not to love?” Leave me alone. My sister would try to intervene and protect me but to no effect. It did not help that I was fairly fearless, and stupid. So rather than back down or lay low, I teased, name called, yelled back and fought with my brother, who was always much bigger, and I always lost. My greatest victory occurred one day when I tossed a metal trash can, adorned with all the U.S. presidents on it, and hit Gordie in the mouth chipping his tooth. I had awarded him the presidential metal of freedom! I caught hell for it, but truthfully I felt it was self-defense and my parents should have been more concerned about him constantly beating me up than my occasional victory against my own fraternal death star. I could use this technique if I was ever in the Israel Defense Force and they needed a Krav Maga instructor.

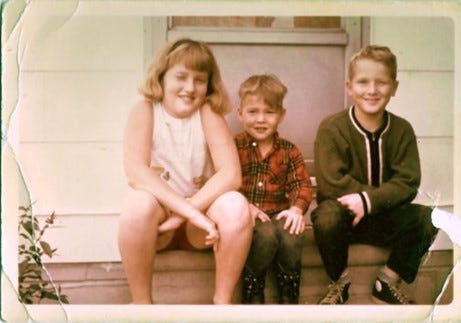

Cindy, me and Gordie at our East Side home:

In any case, our dad would come home and yell at us both. Then we had a meal of food none of us usually liked to eat much and that was part of the somberness along with my dad’s general strict attitude at the table. My brother for instance could not stand drinking milk, but that was required. Eventually chocolate milk was reached as a sort of compromise. I, on the other hand, lapped up milk like the cool cat I felt destined to be. My mom was not a bad cook, but she was not really a good cook. She put together a lot of food rapidly (after she worked), snacking on other food as she prepared our meal, and then sat with us not eating, while we ate our meal. Sliced cucumbers and green peppers as our vegetable, usually, and some form of potato, which was all fine. As we were reminded, people were starving in India, so we were going to eat all of our food just to not let them down.

Since my father liked meat prepared well done, I always found it pretty dry and tasteless. Everything required a heavy pour of catsup. I thought that was how steak was supposed to taste until I was in my 20’s and had it in a restaurant and discovered it tasted good. Of course, there were exceptions, like fried chicken or spaghetti and those foods were my favorites. And my brother got breaded pork chops (which I did not like). There was always plenty of it, so at least it was not like that joke where the guy complains, the food is terrible here; yeah, and such small portions. It was centered around my dad’s taste, and he was a guy who went into the army and gained a bunch of weight eating army food. He said that he thought it was part of his pay, so the more he ate the more he got paid. He made a point of trimming down before he got out. But he might be the only guy in history who went into the army and really liked their food.

Leader of the Pack: The Shangri-Las

I had a gang of kids in my neighborhood and I was their leader. We played sports together in someone’s backyard or the streets: football, baseball, basketball, and hockey on roller skates. In winter, neighbors made little frozen rinks in their backyards for ice hockey. In one of those as a kid, I got bashed in the eye by a guy winding up for a slap shot. Lots of blood and some very scared parents but my vision was not permanently affected, just a few weeks with a taped-over eye. I mostly avoided significant injuries except for the time I jumped off something we called the jinx box in our corner park, Parkgrove Park. I jumped from about ten feet and landed feet first but my momentum carried my hand to the ground where it was, not surprisingly, cut by the many shards of glass lying there. Actually, I was surprised. I should have had more concern about the sea of glass I was jumping into but it was just gung ho Geronimo and then hospital.

A year or so later, when I was ten, I was carving initials in the park bench and was a little reckless making an S. I thought the previous guy’s S was too blocky and did not accurately reflect the S’s curve. Well, my S caused my jackknife to snap shut and nearly take off the tip of my finger. So much for being a perfectionist. I rode my bike home from the park, screamed for my mom as I got to within screaming distance. She saw my blood-covered arm and panicked backing out of the drive running over my bike’s sissy bar while doing so. After that, no more sissy bars for me. It did not turn me off from my eventual date with many dive bars.

Around that same time, I developed a passion for making fires in the alleyways with my friends, and that was a thing for a while because we were able to behold the primordial power of fire firsthand. It was truly a cheap thrill requiring very little capitalization. One kid who used to participate, David Laughlin, was a child of a single mom. Known as “Laugh In” but now he would probably be called “on the spectrum” -- as if we all weren’t. He was a bit different, the kid who would steal money and pay for us all to rent golf carts at the public golf course and who was always getting in trouble. He was also the kid who blew off a bunch of his fingers fooling around with M-80 firecrackers. After that, I became less interested in making our little fires in the alley.

I was a confident child and never afraid of fighting anyone. That was one way to show who was in charge, even in our little childhood world. I suppose sparring with my older, much larger brother was good training for fighting kids my own age. And I was strong while quite young. My uncle was a judo champion and my dad had taken it up and sometimes I would go to their dojo to watch them train. I liked to do push-ups and as a child of nine or ten could do 100 without stopping. Fights were frequent but would usually last just long enough for the winner, me, to be on top of the other person’s chest and having them pinned down in a position where they were helpless and forced to submit, or where I had them in a chokehold and would choke them into submission.

As kids, it was rare to call a friend on the telephone and say you were coming over, or to ask if you could come over. Instead, we would simply go to a friend’s house and call their name in a sing-song voice, “Johnny, Johnny.” Then Johnny would come to the door or else some family member would show up and explain why Johnny was not available. That is how everyone did it, and it seemed to be a tradition that went back some time. Most houses had a front and a side or back door and one of those spots, usually not the front, was designated as the spot where we called.

We collected baseball cards and that meant going to local party stores and stealing them. Why pay retail? My family went to church together every Sunday. I believed in God and to some extent in heaven and hell, but it was not going to stop me from stealing baseball cards. We’d go to the neighborhood party stores, browse around a bit, and then stuff a number of packs of baseball cards, then 10 cents a pack, down our pants before walking out. If this was sin and a ticket to hell, it was probably worth it.

We played tag on bicycles over a several block area or a game called fugitive which also took place over several neighborhood streets and was a sort of team hide and seek. We also played tree tag, which was actually tag mostly in trees or along a fence and involved swinging from branches or climbing to the highest branches and even the roof of the house to escape but never touching the ground. There was little sense of mortality and no parent ever said anything to us unless, say, we were playing baseball on the street and the ball kept landing near their window.

Hurricane: Bob Dylan

Matty Halatsis was from a family of 15 children and lived on the next block. He wanted to be called “The Greek,” so of course no one ever called him that, but he was just Matty or Crazy Matty. He was unpredictable. Once, I loaned him my mitt playing baseball, and he threw it on the roof of the party store whose parking lot we were playing in, for no apparent reason. I made him retrieve it. Once, I went to another party store with Matty and another friend after we had gone to church together, and he got caught stealing a bunch of snacks. Even though he was the one who was caught, we all got into trouble and my parents were called. My father particularly did not like that this occurred moments after we left church. He yelled at me and asked why didn’t I beat Matty up. I didn’t know what to say. The truth is I had already beat Matty up dozens of times and Matty didn’t care. Nor did I disapprove of his stealing. I told my father that since we had just come from church I thought it was un-Christian to hit him just then. My father thought about that and didn’t say anything more.

Matty went to our local public high school, Laura F. Osborn, then into the army. After that, he worked at the Falcon Lanes bowling alley on Van Dyke, on the East Side but not our local bowling alley, and he joined a biker gang that drank at the bar near the Falcon Lanes. He had become pretty badass and not someone I was interested in fighting anymore. One day I heard a great number of sirens wailing and I ran out of my house and saw several Detroit Police cars chasing Matty on his motorcycle down our street. Matty was driving onto the lawns of the houses across the street and trying to use all of the advantages of his bike to evade the police. They didn’t care. They were up there driving on the lawns, steering around the trees. At the corner, however, police cars arrived from all directions blocking Matty’s path, and the cop car behind him rammed him, knocking down his motorcycle and sending Matty flying. Then the cops picked him up and slammed him onto the hood of their car. It’s never a good idea to run from the police if you can avoid it at all.

They were pissed off at Matty for the crazy chase and probably for something else, so of course they were brutal. But the whole neighborhood, including some of Matty’s family who lived just a short block away, had all gathered around, as well as Franky, the biker guy who lived opposite us and whose lawn they had just sped across. Some of the neighbors could be real bitches about their lawns, but in this instance Matty got a pass. There was practically a riot against the police. All the charges were dropped against Matty after the cops were threatened with a police brutality suit. I went inside and wrote my first song, “The Ballad of Matty Halatsis,” to the tune of Dylan’s “Hurricane.” “Here comes the story of Matty Halatsis. He rode a bike and kicked a lot of asses.” But Matty died, too young, about twenty years ago.

We mostly played tree tag at Matty’s house because there was a large apple tree there, good for climbing, which also allowed access to the roof (there were no boundaries), and you could swing from branch to branch or come down near the bottom and stand on the fence that bordered the alley there while still holding on to some branches. The only rule was you could not touch the ground but that happened to Matty’s younger brother, Jimmy in a non-tree tag, tree related incident. Naturally, Matty and Jimmy were good tree climbers with that tree right next to their house. And both were reckless. We used to also play in the back yard of an empty house on our street. This yard was larger than most and had a lot of trees in it. We spent time next door at Dean Rasch’s house because his mom was a single mom, so little adult supervision, and their garage had a little room over it that we used as our club house. That is where we would keep our dirty magazines and other contraband.

One day we were playing in the yard next door and Jimmy jumped from a top branch of a tree, about 25-feet tall. It was amazingly daring, like Tarzan. He jumped and caught on to another branch much lower and swung a bit to slow up before landing successfully. We were all astounded. Except one guy missed it so we asked Jimmy to do it again. He did. This time Jimmy missed the connection with the lower branch, came down hard and broke his arm, horribly. We walked him back to the Halatsis house, delivering him to his older brothers and sisters with our apologies.

At the Hoover Dam: Cindy, Mom, Me (wearing knife), Gordie:

You’re funny! Glad you’re doing this.